1. Introduction

Plastics in fisheries are largely synonymous with fishing gear, and consequently, abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG), including nets, lines, etc., is the largest contributor to seabased sources of marine plastic debris. Since men are dominant in the harvest sector and use boats and gear composed of plastics, loss of gear, especially large nets, is seen to affect them economically. Women, in general, do not go out to sea to fish and hence may not use fishing gear such as large nets, and are often not recognized as fishers. Hence few marine plastic management projects targeting fishers include women, effectively marginalizing their knowledge or needs (Veena and Kusakabe, 2023); few studies actually examine the use and impact of plastics on women in fisheries. Here, we highlight the importance of looking at the problem of plastics through a gender lens, with a primary focus on women in fisheries.

2. Use of Plastics by Women in Fisheries

The dominant use of plastics by women in fisheries is in the postharvest sector. Women fish vendors use single-use plastic bags as they are practical for transporting wet commodities. They use plastic trays and baskets for carrying fish and mats woven of plastic fibre for drying fish as plastics are cheaper. Women, who harvest fish sometimes use small rafts made of thermocole for paddling. However, the exact quantum of plastics used by women as part of their livelihood activities has not been estimated.men in fisheries.

3. Impacts of Plastics on Women in Fisheries

There is considerably more information on the impacts of plastics on women in fisheries, though even here, a lot of it is from scattered news reports and communications during workshop discussions.

Direct Impacts: Fisherwomen are actively engaged in the harvest of shellfish, prawns, and fish and prawn seeds in the Indian coasts in Kerala, West Bengal and Odisha. Around 58% of seed fish/shrimp seed collectors are women (Gopal and Ananthan, 2022). During workshop discussions on women in fisheries (e.g., ICSF, 2022), fisherwomen reported often finding fewer prawns but more plastics in their nets, such as nylon bags, broken nets, straws, and plastic bottle caps. This not only causes lesser yields but also cleaning up these materials consumes a significant amount of their time, which is a time-consuming task apart from causing potential injuries. Gleaning, a large subsistence activity supporting food security, is also carried out by a large number of women, especially in shallow waters. Gleaning amidst plastic has also resulted in an increase in skin diseases among women. In Tamil Nadu, in the Gulf of Mannar coasts, women seaweed collectors dive into deeper waters of around 15m depth without any protective gear except strips of cloth around their fingers and are affected by marine litter that snags onto corals and rocks. In Mumbai, as in other places, women offering prayers to the sea during Narali Purnima have to stand amidst piles of accumulated plastic trash that affects them aesthetically and culturally (Behal, 2024). A number of women also work in the processing sector where plastics are extensively used in packaging. In the case of processing and value addition, the plastics used for packaging or for drying and heat sealing of packages may release volatile compounds that have adverse effects on women working in the sector.

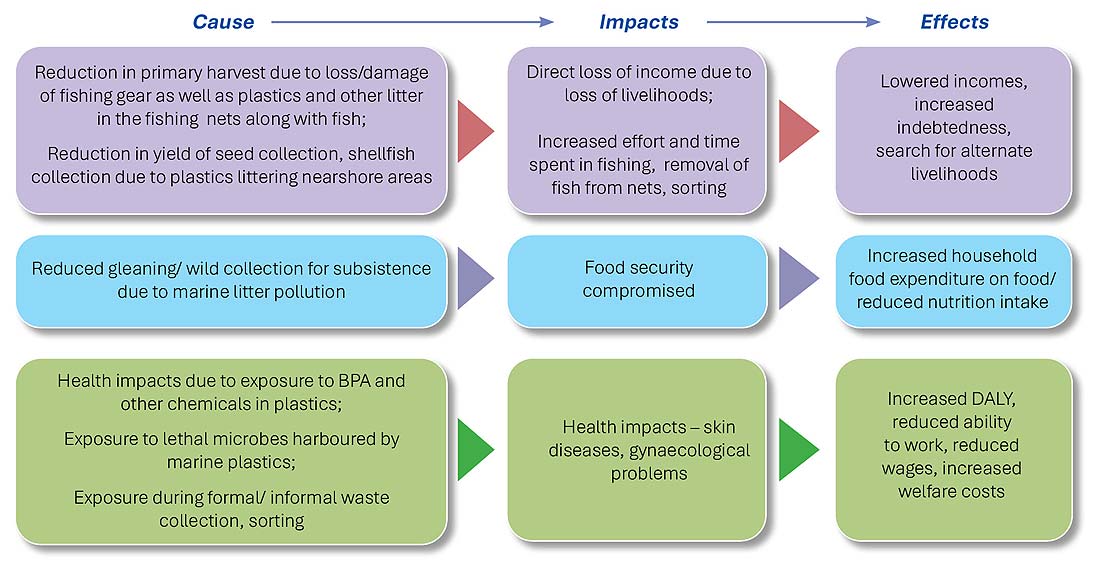

Indirect Impacts: Women in fisheries are also indirectly affected by plastics used by their menfolk. Loss of fishing gear can prove to be very expensive, resulting in loss of livelihoods for both men and women and pushing them deeper into debt. Removal of plastics caught along with fish in nets can result in lower catch and additional time required to clean and repair nets, which in turn reflects lower incomes. The lowered catches by fishermen put pressure on women, who are in supporting roles in the post-harvest sector or home-makers, to find alternate income sources to meet the demands of the family. An overview of the causal chain of the use and impacts of plastics on women in the fisheries sector is presented in Figure 1.

4. Way Forward

Though there is considerable discussion on the generation of marine litter, especially plastics, and their impacts on ocean and coastal resources, discussions on the impact of marine plastics on women in fisheries are few and far between. Based on the above analysis and literature, we propose the following hypotheses and way forward for future research in this area:

1. Economic Impact: Women in fisheries experience economic effects of marine plastic pollution that are distinct from men’s, due to their roles in postharvest activities. For example, women’s reliance on single-use plastics and other tools for vending and processing fish suggests the need for targeted interventions to quantify these impacts.

2. Health Impact: Plastics in fisheries expose women to specific health risks, including injuries and diseases during gleaning and processing activities, but the extent of these risks compared to men remains under-researched. Direct exposure to plastic-related toxins and debris calls for a better understanding of health disparities.

3. Cultural and Social Impact: The cultural and social impacts of plastic pollution, such as disruptions to traditional rituals and community aesthetics, are experienced by women in ways that are deeply tied to their roles in coastal communities. These impacts require detailed exploration to evaluate their socio-cultural significance.

4. Data Collection and Quantification: The current gap lies in quantifying the specific ways in which plastics impact women’s livelihoods, health, and cultural practices. Collecting gender-disaggregated data is essential for framing these effects accurately. Future research should prioritize quantifying these impacts through robust data collection and analysis. Such efforts would provide evidence-based insights to inform inclusive policy frameworks and interventions for managing marine plastic pollution. Women are part of the fresh fish vending and processing sector, which also uses a considerable amount of single-use plastics. Despite a ban on single-use plastics, they continue to be used due to a lack of alternate options. Research conducted in the Mumbai coasts revealed that the majority of the respondents in the fishing community wish to reduce plastic litter and are very much willing to reuse or use eco-friendly biodegradable bags for shopping if such systems are made mandatory (Reshi et al.2022). This is but a microscopic effort but indicates that any effort in reducing marine litter has to have a broader appeal.

5. Scope in the BOBLME II Project

Component 3 of the BOBLME Phase II, being currently implemented by BOBP-IGO in its member countries, focuses on ‘Management of coastal and marine pollution to improve ecosystem health’ in which Outcome 3.1 is ‘Pollution from discharge of untreated sewage and wastewater; solid waste and marine litter; and nutrient loading reduced or minimized in selected hotspots in river, coastal and marine waters’. Among the targets are a) Specific needs of men and women identified and taken into consideration, b) Women and men involved in implementing good practices, and c) Gender disaggregated reporting. For this, it is planned to collect gender-disaggregated field-level data on the consumption and disposal of plastics along the value chain in the fisheries sector. The perceptions of both men and women on how responsible use of plastics can be promoted, as well as potential alternatives, are planned to be collected. Simultaneously, inputs into the impacts of plastics – economic, health, and environmental – will also be collected. This could be built up as a guidance document where gendered information on plastics usage in the fisheries sector, as well as the impacts of plastics disposal, will be available. Following this, an action plan for responsible use of plastics in fisheries incorporating gender-focused interventions can be formulated.

References

- Chacko, Benita, 2018. Maharashtra plastic ban: Tough time for fish, meat sellers in Mumbai without alternative options. Indian Express, April 4, 2018.

- Dimple Behal, 2024. Plastic Perils. https://caravanmagazine.in/communities/impact-plastic-pollution-mumbai-fisherwomen.

- FAO, n.d. Abandoned, Lost or otherwise Discarded Fishing Gear (ALDFG) https://www.fao.org/responsible-fishing/marking-of-fishing-gear/aldfg/en/

- Gopal, Nikita and Ananthan, P.S., 2002. Do women fish? Yemaya, 65: 12-14. https://www.icsf.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Yemaya_65_Do_women_fish_Nikita_Gopal.pdf

- Reshi, Saba N., Neha W. Qureshi, and M. Krishnan. “Awareness, perception and adaptation strategies of fisher community towards marine plastic pollution along Mumbai coast, Maharashtra, India.” India Journal of Fisheries 69, no. 3 (2022): 135-143.

- UNEP, 2021 From Pollution to Solution: A global assessment of marine litter and plastic pollution. https://www.unep.org/resources/pollution-solution-global-assessment-marine-litter-and-plastic-pollution

- Veena, N and Kyoko Kusakabe, 2023. Gender and marine plastic pollution. Yemaya, 66, pp 9-10. March 2023. https://icsf.net/yemaya/gender-and-marine-plastic-pollution/

*This article is reprinted with the kind permission of the Bay of Bengal Inter-Governmental Organization (Link). It is published in BOBP Breeze, A Quadrimester Newsletter, September-December 2024 Vol. III; Issue 3:31-33 and is available at: https://www.bobpigo.org/publications/BOBP%20Breeze%20%20A%20Quadrimester%20Newsletter%20%20September%20-%20December%202024.pdf

Authors

- Dr. Ahana Lakshmi, BOBLME Hub Coordinator

- Dr. Nirmala K, International consultant-BOBLME

- Mr. Rajdeep Mukherjee, Policy Analyst, BOBP-IGO