Vietnam has seen its economy undergo many drastic changes during the past 40 years, going from a centrally planned economy to a market-driven one. Since the transition to a market-driven economy, many studies on the economics of commodities have been conducted.

Revenues of fishery products have been increasing these past few years in Vietnam. Tuna is the sea-commodity with the highest added value for export and its business provides an income to more and more Vietnamese (USD 653 million in 2018, Vietnam Association of Seafood Exporters and Producers [VASEP], 2019 cited by USAID 2020). That’s why the Vietnamese Ministry of Sciences and Technologies recently funded a couple of research projects on value chains (VC) in the fishery sector. Among these studies was the study by Mrs. Nguyen Dang Hoang Thu towards her PhD thesis.

Understanding a value chain enables its improvement and helps overcome bottlenecks. Yet, the existing literature on the value chain of tuna in Vietnam does not take gender into account.

Conducting a gender analysis will help build a picture of the role of women and highlight gender disparities, and hence be a good ally to reach equality. It’s also a tool that can help assess the differences between men and women’s roles and who gets the power over resources, therefore helping find the pivots on which to work to reach equity or at least reduce gender disparities. The literature commonly reveals the fact that women are usually working in the post-harvest nodes of the value chain (Weeratunge et al 2010) (WINFISH 2018) (Biswas 2018) (Fröcklin 2013) (Lentisco 2015). This is why we conducted a gender analysis on the purchasing node of the VC.

This gender research was the topic of my master’s thesis (Sundar Raj, 2020) and it also produced the material needed by Nguyen Dang for a chapter of her thesis (DHT Nguyen, 2020). Parts of the study are also reported in our recent paper (DHT Nguyen et al 2020).

Forty tuna traders and middle-persons were interviewed in Tam Quan and Quy Nhon fishing ports in Binh Dinh province. They were selling only three species of tuna: yellowfin (Thunnus albacores), bigeye (Thunnus obesus) and skipjack (Katsuwonus pelamis). The first two are sold in Tam Quan port on the same market and are considered as one while skipjack tuna is sold in Quy Nhon port.

Two professional types in the sale of fish interested us: trader and middle-person.

Traders are individuals who buy fish from the fishers and fishing boats and sell it to middle-persons. The roles of middle–persons vary according to the species and business.

In the yellowfin and bigeye tuna business, middle-actors are contractually bound to processing plants for which they buy fish at a price given by the plant. In the skipjack tuna business, the middle-persons have, in addition to being buying agents for processing plants, the role of wholesalers for local markets. For local markets, they buy the skipjack directly from fishing boats and resell it to other middle-persons. Middle-persons own companies that are usually run by couples, whereas traders work alone.

In our study, traders only operated in Quy Nhon. In that city, both traders and middle-persons are women.

In Tam Quan, there are no traders but only middle-men and middle-women.

The questionnaires were designed based on three gender analysis methodologies:

- USAID’s six dimensions: (i) access to assets, (ii) practices and participation, (iii) knowledge, beliefs and perceptions, (iv) legal rights and status, (v) power and decision-making, (vi) time and space. This was based upon the Harvard and Moser frameworks (see USAID (2018) for details);

- Moser’s three types of roles: productive, reproductive and community management; and

- The Social Relations Approach.

The objective of this study was to identify women’s roles by assessing gender disparities in the purchasing node of the tuna value chain in two cities of Binh Dinh province: Quy Nhon and Tam Quan. The hypotheses were that the main differences were: (1) the daily schedules, therefore the link with the triple role, and ownership; and (2) women would be left with lower value goods since accessing loans was harder for them and they might be subject to their husband’s decisions and denied ownership but also that men may have access to more customers, and to higher-value products to sell (Fröcklin, 2013).

We observed that the main gender disparities, from which all the others arose, pertained to two factors, namely the professional type (trader or middle-person), and the species of tuna traded.

With respect to the professional type, no man is working as a fish trader which is considered an inferior position to a middle-person and entails less responsibility, providing lower revenue.

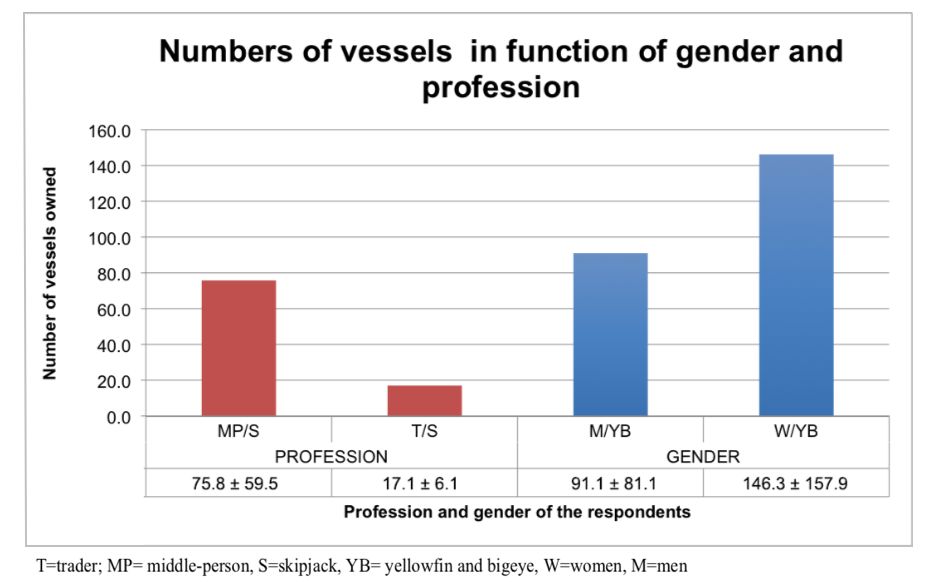

For the species of tuna traded, men are only found in the yellowfin and bigeye tuna business. All the skipjack tuna middle-persons and traders were women. Men tend to choose a softer market that doesn’t require much detail. Other differences are found in the reasons for choosing this profession: tradition and relation with fishers and processors lead the men to being middle-persons, while what drew women to selling yellowfin and bigeye rather than skipjack tuna is the ease of handling and fewer work hours. In terms of the quantities of yellowfin and bigeye tuna traded, men deal with lower volumes of tuna than women, regardless of the job and species. Otherwise, there is no significant difference between middle-men and women in the yellowfin and bigeye sector.

Some assumptions were made for the research objectives, saying that the major disparities were more likely to be found in the access to assets, practices and participation and power and decision making dimensions of USAID’s approach. The hypothesis that women are denied access to capital is disproved by a few facts. First, women have on average more boats than men, which is in line with the fact that they trade bigger quantities of fish. Second, it is more common for a woman to access a loan. Men are able to self-finance their businesses thanks to the traditional system providing them bequests and legacies from their parents. The fact that more women are benefiting from credits from banks shows that there is no connection between having access to loans and therefore being able to invest to get higher value products. Yellowfin and bigeye tuna, being destined for export, have higher profits resulting from trade that is higher in value than that of the skipjack tuna trade. Since men are only working in the yellowfin and bigeye tuna business, we can conclude that they operate in a better market and have bigger customers; also they only trade with men, where women deal with both genders. The diversification of customers is an asset for the women who benefit from greater options and therefore resilience. It refutes the theory that men have more buyers.

The salaries are equal for the same jobs, yet, men are earning more only in the yellowfin and bigeye tuna business thanks to their physical advantage of usually being stronger and therefore able to manipulate the larger fishes Yet, women working in the this business have lower revenue than men and operate different activities that do not involve directly working in fish trading such as selling oil for the vessels, ice for the storage or any other kind of gear that can be needed for fishing.

All women interviewed reported having no time for themselves, every second being either spent on work or managing the household. Despite that, they still loved their profession: no interviewees mentioned that they didn’t like their job, despite the lack of free time. The prestige that comes with good income was the only factor that accounted for job satisfaction.

Women were more likely to have long working hours and little free time since they had to ensure their two roles: productive and reproductive. Here, women did not have triple roles; they were in charge of the household and most of the administrative tasks of the business. They were perceived as better at negotiating than men since they showed patience and diligence in their business transactions.

Unlike what one might think, the role of community managing falls to the men. Men mostly evoked “a good relation with the customer and suppliers” as the reason they started their job. Typically, most of them spend their free time with their friends drinking coffee and beer, or, as they call it “socializing for the good of the business”.

Overall, this study reveals that women in the purchasing stage of the tuna value chain in the southern central provinces of Vietnam play an important and indispensable role.

* Rachel Sundar Raj has a master degree in bioengineering from Gembloux Agro-Bio Tech, University of Liège, Belgium. For her master thesis she conducted this study in Vietnam in collaboration with Mrs. Nguyen Dang Hoang Thu (PhD student at Liege University and a Lecturer at Da Nang University) in 2020.

References

- Biswas, Nilanjana. 2018. Towards Gender-Equitable Small-Scale Fisheries Governance and Development: A Handbook. FAO. UN. https://doi.org/10.18356/e999fb85-en.

- DHT Nguyen, R Sundar Raj, Q Cao Le, TMH Le, TT Nang Thu, P Lebailly (2020). Gender Analysis of the Tuna Value Chain’s Purchasing Stage in the South Central Provinces of Vietnam-Case Study of Binh Dinh Province, Asian Social Science 17 (1), http://www.ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/ass/article/view/0/44485

- Fröcklin, S., Castro, M. D. L. T., Lindstro ̈m, L., & Jiddawi, N. S. (2013). Fish Traders as Key Actors in Fisheries: Gender and Adaptive Management. AMBIO, 42, 951-962. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-013-0451-1

- Lentisco, Angela, et Robert Ulric Lee. 2015. A Review of Women’s Access to Fish in Small-Scale Fisheries. Food and Agriculture Organization, 45p, http://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/385279/.

- Moser, C. O. (1993). Gender Planning and Development: Theory, Practice, and Training. London: Routledge. Retrieved from https://www.routledge.com/Gender-Planning-and-Development-Theory-Practice-and- Training/Moser/p/book/9780415056212

- Thu, N. D. H., Quyen, C. L., Hang, L. T. M., Tran, N. T. T., & Lebailly, P. (2020). Social Value Chain Analysis: The Case of Tuna Value Chain in Three South Central Provinces of Vietnam. Asian Social Science, 16(8). https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v16n8p43

- USAID (2018). Gender Research in Fisheries and Aquaculture: A Training Handbook. https://www.seafdec-oceanspartnership.org/resource/gender-research-in-fisheries-and-aquaculture-a-training-handbook/

- USAID (2020). Tuna Value Chain Analysis for Binh Dinh Province, Vietnam. Retrieved from https://www.seafdec-oceanspartnership.org/resource/tuna-value-chain-analysis-for-binh-dinh-province-vietnam/

- Weeratunge, N., Snyder, K., A., & Sze, C. P. (2010). Gleaner, Fisher, Trader, Processor: Understanding Gendered Employment in Fisheries and Aquaculture Fish and Fisheries. Fish and Fisheries, 11(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-2979.2010.00368.x

- WINFISH. 2018. Gender Analysis of the Fisheries Sector. General Santos City, Philippines. USAID. https://www.seafdec-oceanspartnership.org/resource/gender-analysis-of-the-fisheries-sector-general-santos-city-philippines/